- Edward “Ted” Angel

- Leonard Hayes Baines (d. Sept 1940)

- Horace “Horry” Bainger & Sylvia Bainger nee Paul

- Ronald Charles Barfoot (d. Sept 1940)

- Alfred Douglas Bedford (d. Sept 1940)

- Clarence “Ben” Bennett

- Squadron Commander James Bird RNAS retd

- William Alfred Blond (d. Sept 1940)

- Ivy Dorothy Sybil Blythe 1919 – 2010

- Oliver Boland (d. Sept 1940)

- Bernard “Bernie” Byrne – 1926 – 2021

- Alfred John Cook (d. Sept 1940)

- Leslie and Vicky Cooper

- George Edward Copson (d. Sept 1940)

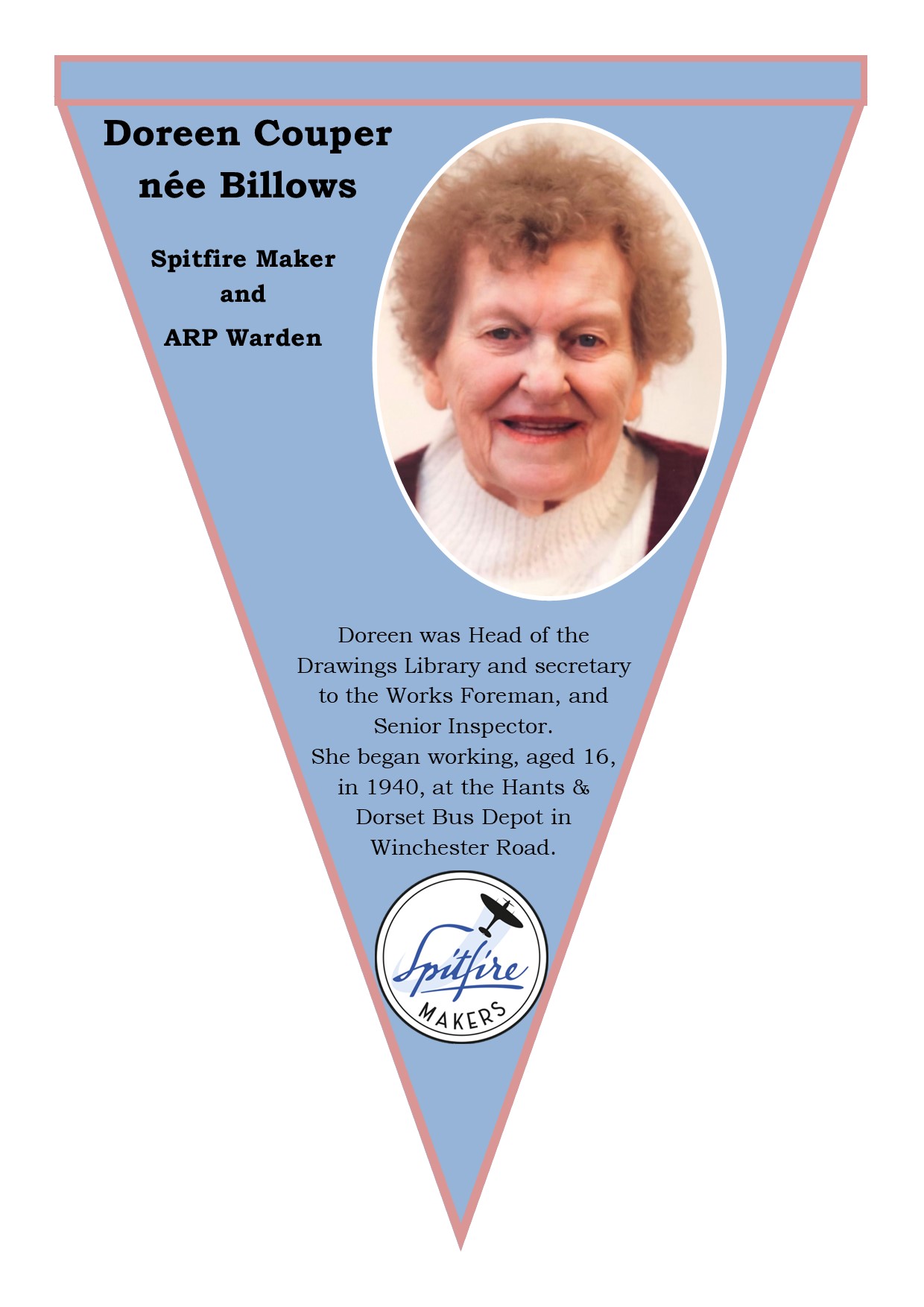

- Doreen Couper nee Billows – Spitfire Maker & ARP Warden

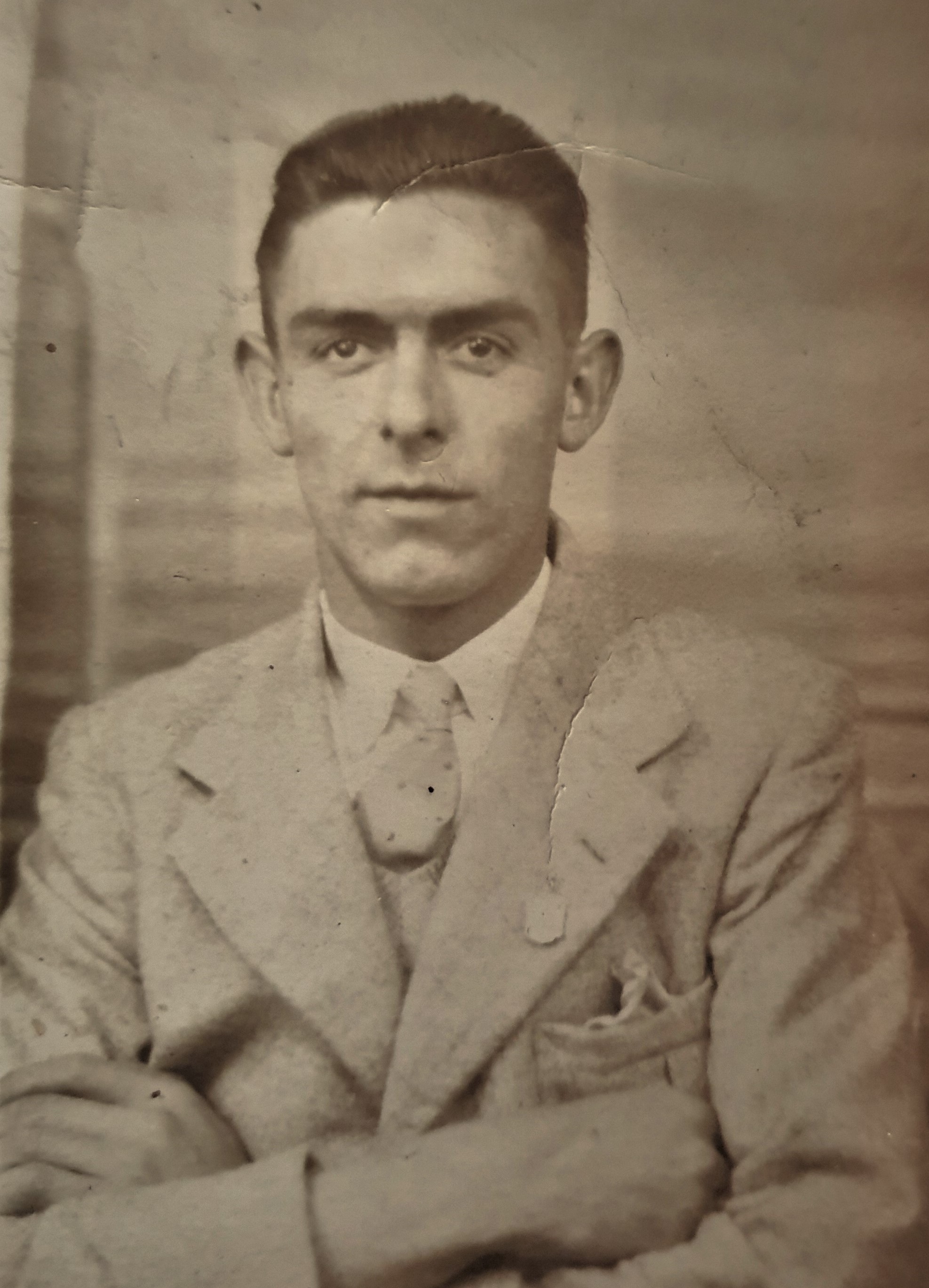

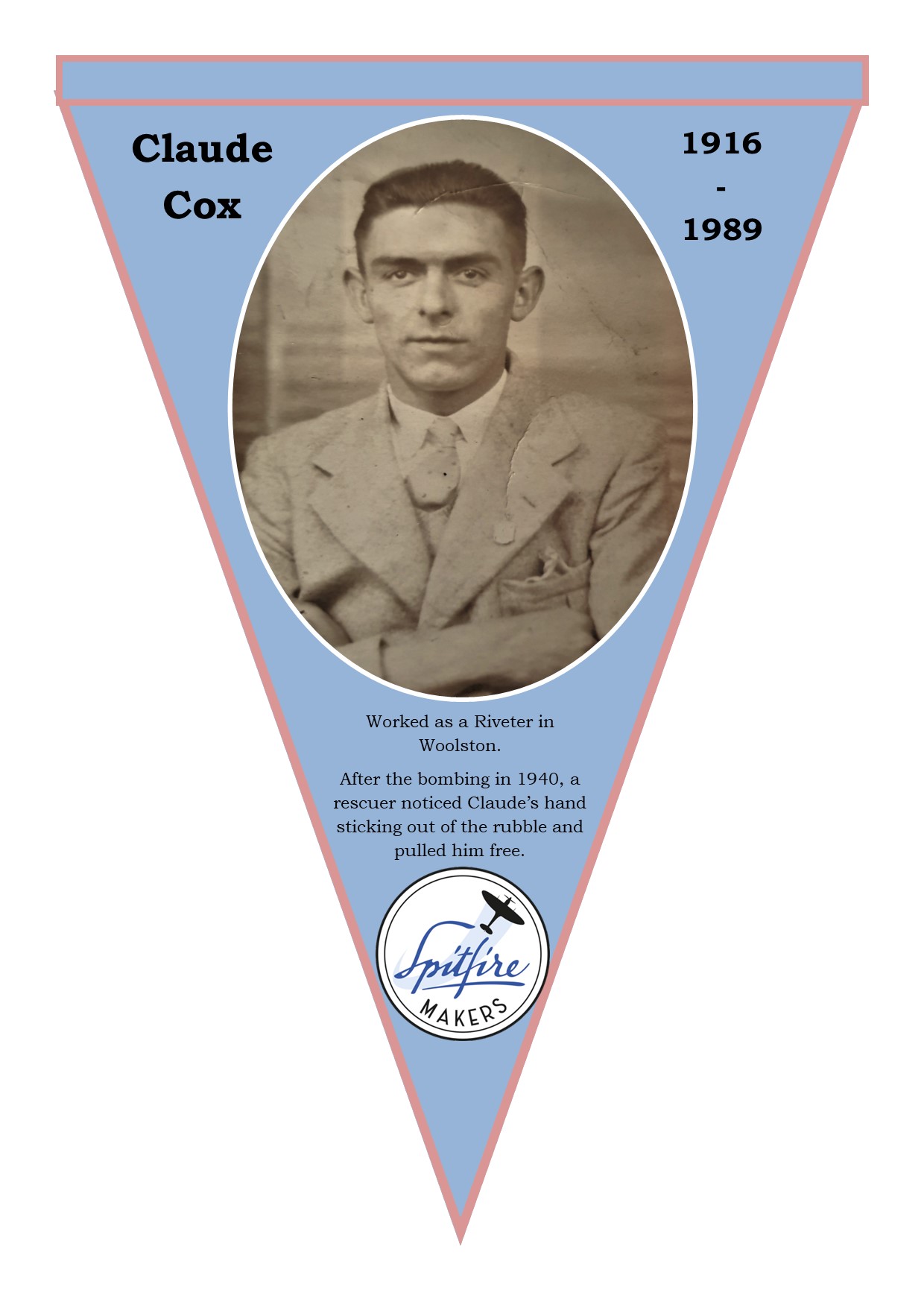

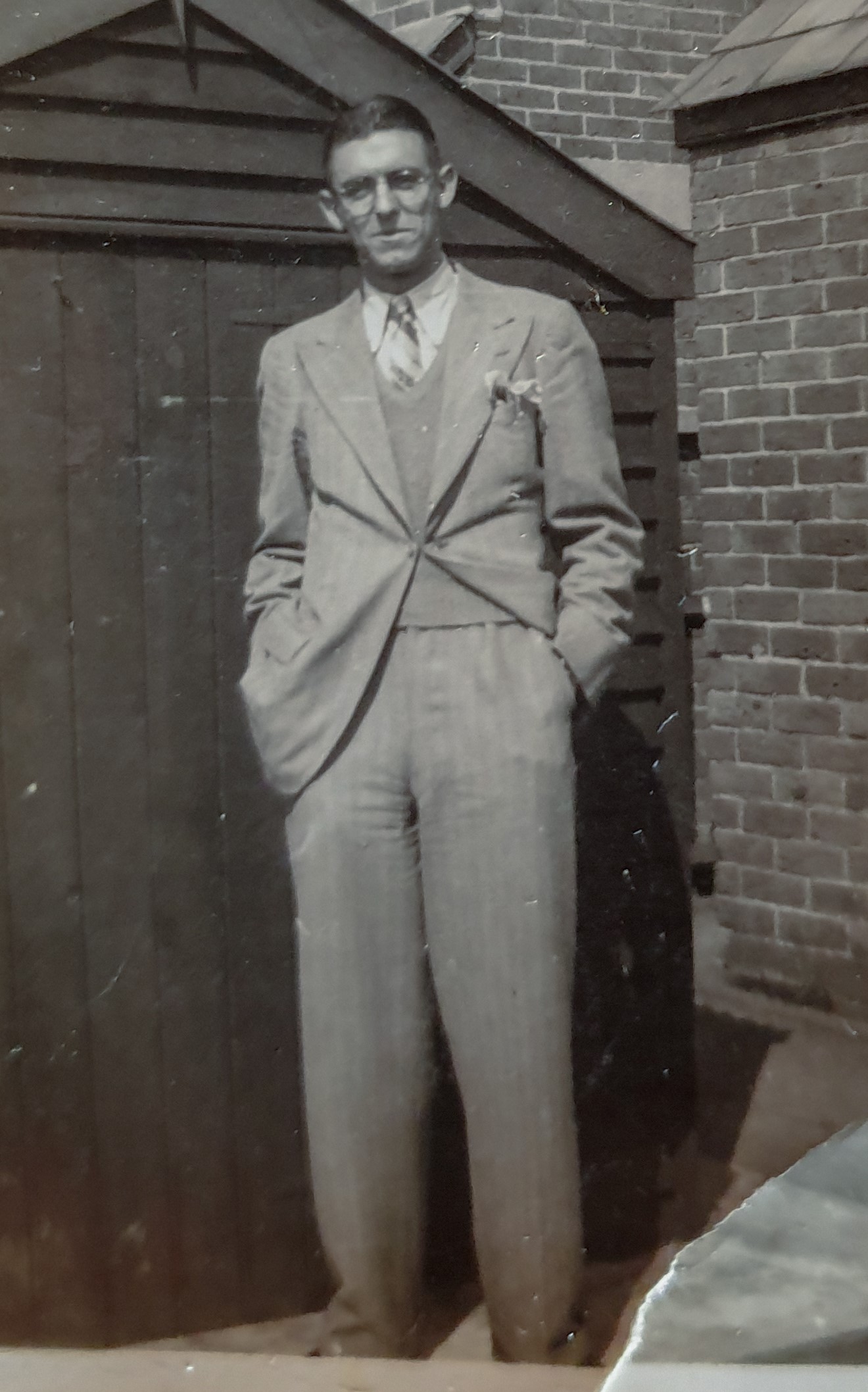

- Claude Cox 1916 – 1989

- Leonard Herbert Cox (d. Sept 1940)

- Douglas Cruikshank (d. Sept 1940)

- James Curtis (d. Sept 1940)

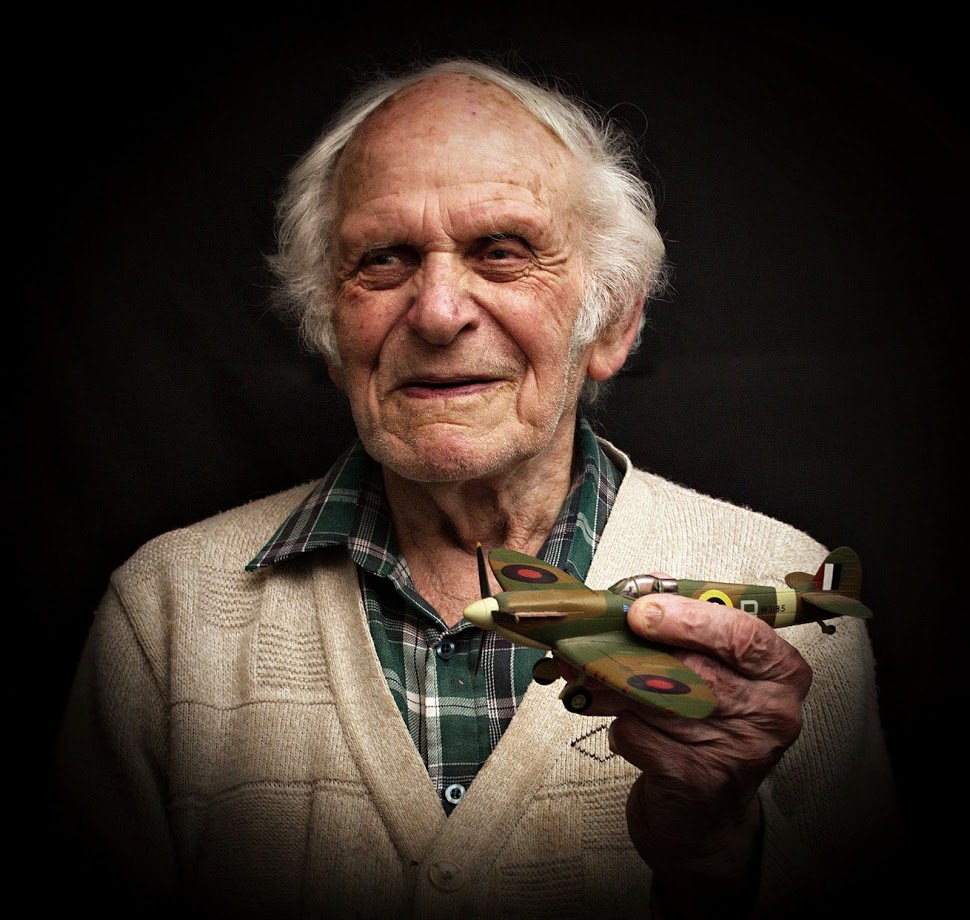

Edward “Ted” Angel

Images courtesy of Sarah Penfold, The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Edward “Ted” Angel is the grandfather of Spitfire Makers team member Sarah Penfold.

Sarah’s granddad Ted Angel (known by his colleagues as ‘Curly’ because of his hair) started as an apprentice at Supermarine on 26th March 1936 building Walrus and other flying boats before moving on to building Spitfires.

After the bombing of the Supermarine factories in Southampton, Ted was transferred to work in Reading where a dispersed production hub had been set up.

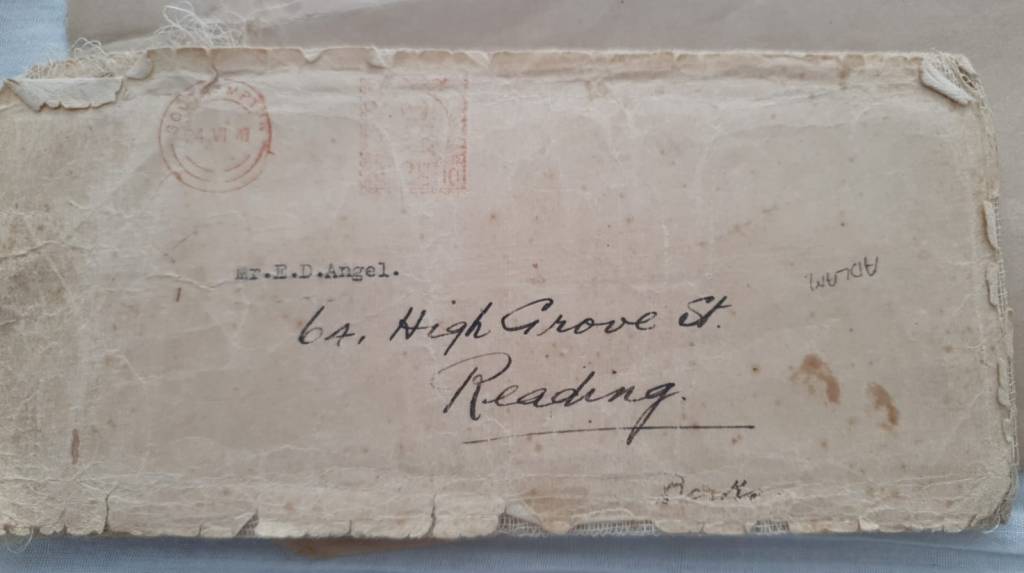

His apprenticeship papers were sent in this reinforced envelope to his digs and the papers themselves are kept at Solent Sky Aviation Museum.

The indenture letter, 5 years after Ted ‘signed on’ to inform him that he had completed his apprenticeship. Ted was by this time working, possibly at the requisitioned Vincent’s Garage, near the station in the centre of Reading.

Interesting to see they were still using old headed notepaper with Woolston crossed out and Chandlers Ford inserted for the telephone and, in the address,Southampton replaced by Hursley Park.

The name, Supermarine, was adopted in early 1916 when Noel Pemberton-Billing sold his share in what was Pemberton-Billing Ltd. to Hubert Scott-Paine. It was the original telegraphic address for the company but here this is shown without the final e and is now directed to Winchester, not Southampton.

The audio below is a short snippet from an interview that Ted gave to the team at Solent Sky Museum in 2016. Ted shares his very moving memories from being caught up in the bombing of the factory. At the time he was in his early 20s. Three of his fellow apprentices – or ‘shop boys’ were killed in the raid including Douglas Cruikshank and Kenneth Doswell who were both 14 years old.

Audio courtesy of Solent Sky Aviation Museum. Please do not reproduce without permission

Sarah has volunteered at Solent Sky Museum since the passing of her Grandad as she told him that she would keep the Spitfire clean for him.

To read Sarah’s tribute to her grandfather Ted please click here

Leonard Hayes Baines (d. Sept 1940)

Image by The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Leonard was a labourer at Supermarine. He was 34 years old when he was killed in the bombing raid on 24th September 1940. Leonard is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

Horace “Horry” Bainger & Sylvia Bainger nee Paul

Images courtesy of Michael Bainger and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Michael Bainger writes……

Horace joined Supermarine at Woolston in 1934 and worked on the prototype Spitfire, being at Eastleigh with his colleagues for K5054’s test flight on 5th March 1936.

He fitted the radiator and cooling system and later was an armourer. He helped to test the effect of dome headed rivets against flush rivets by gluing split peas onto the flush rivets. After the bombing he went to Eastleigh for the duration.

His wife, then still Sylvia Paul, was based at Cunliffe Owen and was a progress chaser for parts from the dispersal outlets, liaising with Pitters Transport, West End, Southampton for collection and distribution.

Ronald Charles Barfoot (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Ronald was an Apprentice Aircraft Electrician at Supermarine. He was 18 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. Ronald is buried in West End Old Cemetery, West End, Southampton.

Alfred Douglas Bedford (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Alfred was an Aircraft Assembler at Supermarine. He was 28 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. Alfred is buried in Hollybrook Cemetery, Southampton.

Clarence “Ben” Bennett

Clarence Roy Vere “Ben” Bennett was interviewed for the Nuffield Theatre’s “Out of the Shadows” project in 2018 with his niece Maureen Prince, also joining in.

Click below to read the full transcript of the interview:

He recalled, I had two brothers, two sisters. I just grew up, went to Sholing School.

“Eventually we moved out to Titchfield where mines were dropped on us and we … the bungalow we were living in was sliced in half…Took the top of the cottage right off. We were in a garage in Titchfield Hill but we wasn’t there long and we moved back to Hamble.”

“… we got not bombed out, mined out, they dropped mines. One mine dropped one side of the thatched cottage which made a hole in the ground and you could have dropped about six double decker buses in there with no trouble. It was soft ground and the other one landed with a parachute on a fir tree and we had to walk under it because there was fence each side for fields and we had to walk under the blooming mine.

Research shows that Ben’s “garage in Titchfield Hill” was the Priory Garage (still in business under the same name on the A27 just outside Titchfield) and was clearly being used to make or, more likely, repair a variety of Spitfire parts.

Click below to read more about the Priory Garage in “Titchfield Voices”:

Ben added, “I went from school to Hamble and ‘cos of the bombing, they were frightened that if they bombed Hamble, everything would be lost so they (AST Hamble) decided to move different sections to different places. We were moved to Titchfield Hill. We wasn’t there long, I said, before the Germans dropped mines, not bombs, mines, on us.”

The bombing of Woolston

Ben also remembers witnessing the bombing of the Supermarine factories in September 1940.

Asked whether he was frightened Ben replied, “No, I was a kiddy, you don’t not really feel frightened when you’re … Not really unless something lands right alongside you, you know, you don’t realise what’s happening. I was only 14 at the time.

Did you take shelter?

Clarence: No, I just stood there and just watched it happen.

Amazingly brave at 14.

Clarence: Well you’re not brave, you just don’t realise … you’re only a nipper at the time, you think “what’s going on?” you know… I know it was a lovely sunny day. We had a lovely hot summer that year, 1940.

Ben’s work at AST

After getting bombed out of the cottage in Titchfield, Ben moved back into Southampton and his mother’s house in South East Road.

He said, “I went back to the aerodrome, to AST, Air Service Training, and then I started out learning to be a sheet metal worker. I suppose I done about two years learning, and then they approached me, the Management and they said, “We think you’re prepared to do the sheet metal working on your own.” ‘Course you’ve got a mate, so I said, “Yes” and so I went on to there and I worked on to there until 1944.

“To Hamble, we had to cycle there and back. You know, push bike, you know. I can’t remember the time we started, I suppose about 7 o’clock or half past seven I should imagine and worked up to 5 o’clock.

“I was skinning, what we called skinning. A sheet metal worker, Spitfire wings. Now, Spitfire wings, if you want to know, were riveted on top and the plates underneath was pop riveted ‘cos they couldn’t get to hold her up see? The bottom of the Spitfire wings were pop riveted. At the first part, they had four machine guns and the machine guns, when they went into action, had a cover on them, a felt was the name. So that when they fired, they slowed up a bit because they broke the felt for the air. They eventually went on to have two cannons, one on each wing so therefore we had to then make domes because the cannon protruded below the wing, so we had to make a dome to cover that up.

Images – Spitfire Mk1 showing red felt covering guns on wing and Spitfire wing with cannons and blister

Asked if he was working from drawings her replied, “No, there were no drawings as far as we was concerned. The Spitfire wings … one end in the hanger they fitted, they renewed the ribs, for that was nothing to do with me, and then they shifted to us and we what you called skinned them.

“I learnt the trade through … I think he was Welsh. He was a Communist and he learnt me with the trade and he presented me with a hammer and sickle badge, and I took it home and my mother created bloomin’ hell ‘cos I took this badge home [laughs]…. mother wouldn’t let me keep it [laughs].

“…, but he taught me well and then I was asked to go sheet metal working myself, which I did. ‘Course I was supplied with a Mate, as you drill. I drilled a hole right through me finger down there once [laughs].

“Some metal was already on there and sometimes there was none at all and you had to do its plates, and you’d drill ’em in and fold them up and ’course you got to mark off for the doors to fit in for the machine guns. Then you’d take that off and then you’d do the other side which was under the plane. Then you would take that off when you had finished it and, put it one side and then put the top of the wing back on and then it was riveted up. That was the Riveter’s, a hold it up job, so they put the little rivets in and ‘brrrrr’, ‘brrrrr’ and when they’d finished that, then we would put back the bottom of the wings and they were pop riveted. And they went on for four machine guns and then afterwards they used cannon and of course you had to make domes because the cannon protruded lower than the wing, so you had to have to a dome over the bottom of the cannon.

The hangar, one side of it was all women working on spares, cleaning them or I suppose repairing them or anything. This sort of factory was the wings. They were brought in and if the ribs were damaged they were repaired and then they were brought to us and then, what we called skinned them, sheet metal work. And that was ‘B’ hanger.

“Ginger Alford was the foreman, my brother-in-law, he was in another part on top of the aerodrome and I think what happened, all the damaged planes come in by lorry, repaired, and I think women flew them from Hamble Aerodrome to where they had to go. I think they were women (ATA) pilots who used to come and collect them up and take them to the aerodromes where they had to go.

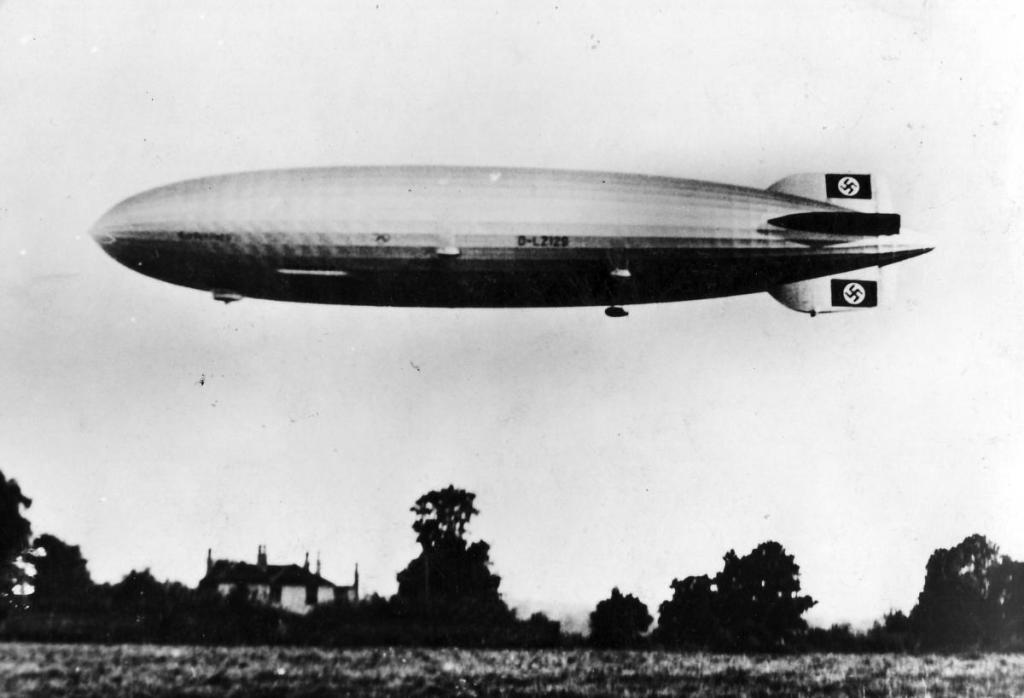

Zeppelins over Southampton

There are well documented accounts of German airships overflying Southampton and Portsmouth in the years before the war. Ben remembers one such occasion and also the visits by German flying boats catapulted from German transatlantic liners while still in the Western Approaches and bringing the mail to their post room which was on the ground floor of the Supermarine building.

“I wouldn’t like to say what year it was, could have been 1937, I wouldn’t swear on the dates, but I was on Weston Shore because my brother had a business down there and I saw a Zeppelin come over Southampton Docks, fly down towards the Isle of Wight and away. Now, it was obvious that that Zeppelin must have taken photos in any case, and that was it. It just seemed to fly over and away, so where he flew or where he come from … well, I expect he came from Germany, he may have flown over Portsmouth, I don’t know, but I know he flew over Southampton. He flew over the Dock area and that was that. I would say that was about 1937 I should think.

“…and the German mail used to come in there and …They knew exactly where the factory was. There was no …they knew where the factory was.”

The flights of the airships were raised in the Commons as a national security threat. Photos taken from the airships were referred to as ‘Hitler’s holiday snaps’ and it is quite likely that the German mail pilots who anchored their seaplanes in the Itchen returned a few years later … in Luftwaffe bombers.

Ben shortly after his 95th birthday

Ben spoke with Spitfire Makers chair, Alan Matlock, when he came to our Spitfire Makers launch event in the Shirley Parish Hall in February 2020.

“I showed Ben the jar of mixed Spitfire rivets that I had been given by George Fuller, a young lad growing up in Hook near Warsash during WW2 who would be allowed to pick up the dropped rivets from the floor of Solent Court Barns, Chilling Lane, where Spitfire wings were being repaired. Like the Priory Garage in Titchfield where Ben went to work, the Barns were most probably an outpost of AST in Hamble.

“With great enthusiasm, Ben told me all about the different rivets that were used in the production of the Spitfire: the ones of different lengths for attaching the wing and fuselage panels, the heat-resistant ones that were used closer to the engine.”

12th May 2020 – Michaela Lawler-Levene on Facebook

Clarence ‘Ben’ Bennett was also nominated as a recipient of a special VE Day cream tea. Ben was just 14 when he mended Spitfire wings during WW2. He would cycle everyday between Woolston and Hamble. At the launch of Spitfire Makers Ben viewed a jar of WW2 rivets and explained what each was used for in the manufacture of the iconic plane. Our best wishes and thanks go to Ben during this lockdown.

Sadly, Ben passed away in 2020. A true Spitfire Maker whose memory lives on!

Squadron Commander James Bird RNAS retd

Owner of Park Place in Wickham, Hampshire. Became General Manager of Supermarine in 1941

William Alfred Blond (d. Sept 1940)

William was an Aircraft Electrician at Supermarine. He was 34 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on 24th September 1940. William is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

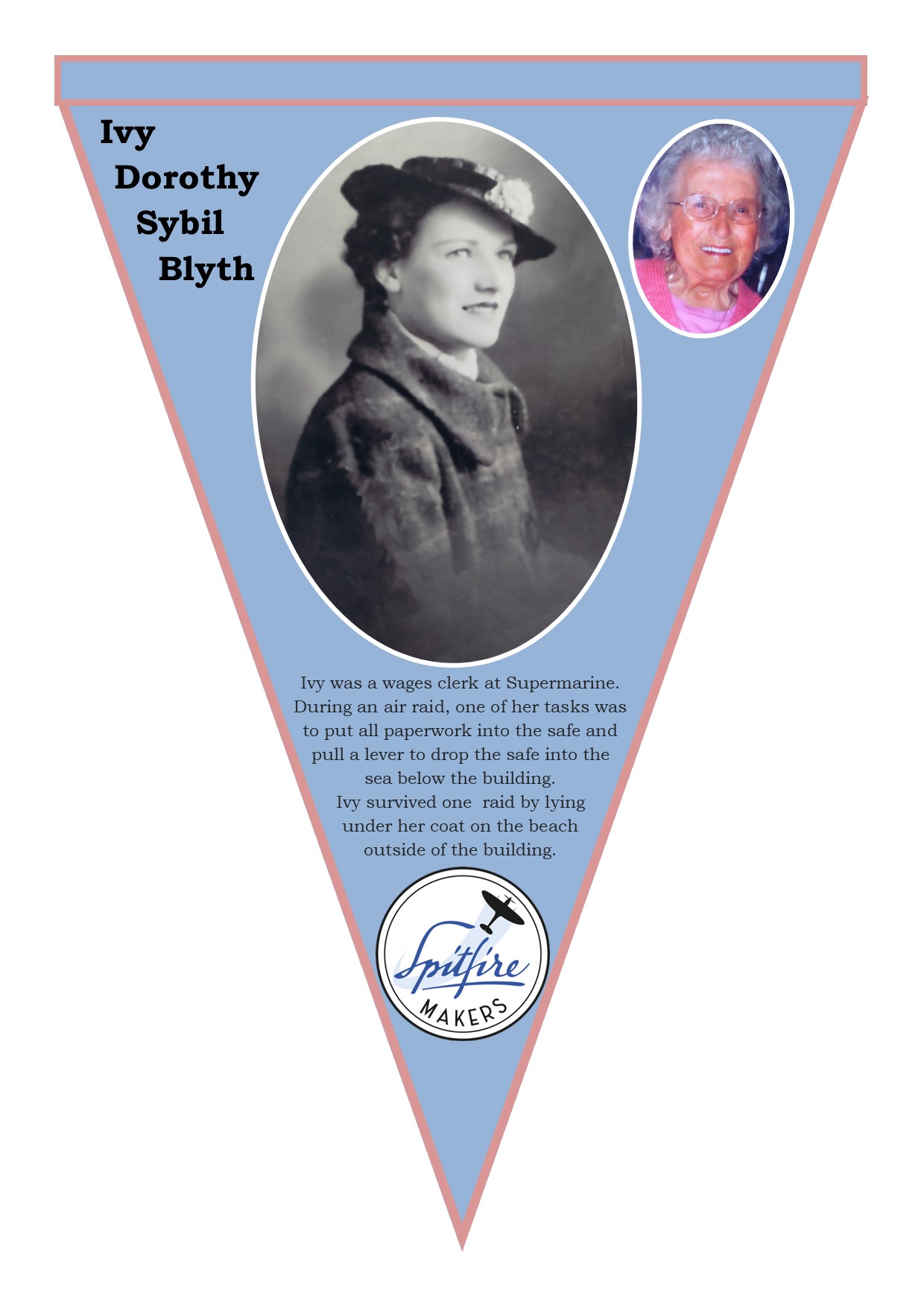

Ivy Dorothy Sybil Blythe 1919 – 2010

Ivy aged 18, 80 & 90years 10months – Images courtesy of Eddie Smith

Ivy’s grandson Eddie Smith writes….

My Nan Ivy, was born on 14th August 1919. She was married in 1939 to Eric Noel and carried on working at least until after my mum was born in 1943. At the time of her working at Supermarine she may have lived in Manchester St in the city. We think she later moved to Arthur Road, Shirley, Southampton but had to move out when the house became uninhabitable after a fireball went up through the hallway and stairs one night during a raid. An incendiary maybe. I don’t know the dates of the entries but mum thinks they went to Shirley Road from Arthur Road.

Nan was a keen cyclist since a small girl right up till she was 71 when her knees gave her too much gyp. She was very sporty and did play netball as well as running. After the war she worked at Follands in Hamble in the offices and was in the netball team so I wouldn’t be surprised if she was in a team at Hursley.

Eric her 1st husband was a tail gunner, got shot down a couple of times but went all through the war. He was never the same after the war, maybe PTSD and they divorced when mum was about 12. He worked at an aircraft factory also in Hamble, they used to cycle to work together. Her 2nd husband Edward Dear, who she married in 1959, was in the home guard throughout the war and was based in Woolston I believe guarding Vospers where he was a plater.

We don’t know if Nan worked before Supermarine or dates of starting and finishing. She was there during a daytime raid on the factory. She told me she could see the plumes of water coming down the river towards the factory as early bombs traced a line to where it was. She was a wages clerk and their job was to quickly stuff all the paperwork into a big safe on the wall if there was a raid then pull a release lever that dropped it into the water under the offices.

The day of the raid after ditching the safe she ran out with all the others, grabbing a younger girl from the stairs on the way who had tripped. They ran down the beach to where the floating bridge used to dock then lay in the shingle cuddled together under nans big coat she had made herself out of an army blanket. She could see straight up Portsmouth Rd as she peeked from under the coat. A big articulated lorry had pulled up outside the cinema. The driver grabbed a young lad out of the passenger side and they both lay under the lorry bed for shelter. She watched as the roofs lifted off the walls of the buildings with the blasts. They got smothered with flying stones from the beach that shredded their stockings and her coat as though a knife had slashed it she said. When the raid died down they looked up the Rd and the lorry had been turned upside down by the blasts but the driver and the lad were unharmed, both sat in the road having a cigarette.

Up until about 8 yes ago I used to use an aggregate yard that was on the site of the Supermarine works, it’s closed now as unsafe after being hit by a ship. Whilst talking to the weighbridge man one day he mentioned to stay away from the far side of the yard as he needed to make up a cover for an old manhole that was oversized. When I questioned him as to why it was so big he said no one knew but he said it had tracks down the side like runners of a lift but was too small for a lift and they went straight down into the water underneath. Maybe that was the safe shaft ?

Oliver Boland (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Oliver was an Instructor (Tool Maker) at Supermarine. He was 40 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 26th September 1940. Oliver is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

Bernard “Bernie” Byrne – 1926 – 2021

Photographs and information kindly provided by the Byrne family. Pennant by The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

In January 2021, Rob Byrne contacted Spitfire Makers with the sad news that his father Bernard had passed away. Rob was hoping that we could help to arrange a flypast at his dad’s funeral. Sadly we were not able to help him at that time but Bernard is definitely one of the amazing Spitfire Makers who we want to commemorate.

Rob Byrne writes- “My dad Bernard (Bernie) Byrne passed away last Thursday . Working throughout the war from 1940 in the Supermarine Flight Shed at Eastleigh Aerodrome , he survived the Luftwaffe bombs and stranding but he could not survive Covid-19.

He was one of the last of the special people that made the iconic Spitfire that alongside the Hurricane saved the nation from the nazi tide.

After the war he was one of the Hampshire Aero Club team that in the 50’s and 60’s flew and maintained G-AIDN which took part in many air races , including the 1959 Kings Cup in Paris.

A normal working class chap from an Eastleigh council estate, yet he led a remarkable life. It’s a big ask I know but his final journey to Wessex Vale Crematorium is on Wednesday 17th February at 10-45am. If any pilot owners plan to be in the skies over South Hampshire around that time , would it be possible to fly by and maybe tip your wings as an acknowledgement not only of my dad but of that indomitable generation. Please Facebook message me if you’re able to help. Thank you.”

Apprenticed, aged 14, in 1940, Bernie worked in the Supermarine Fight Shed at Southampton Municipal Airport testing new and repaired Spitfires and later, Seafires.

He was a wartime ARP messenger and from 1956 helped the Hampshire Aero Club maintain and fly their 2 seat Spitfire.

Bernie was an inspector for British Aerospace, Hamble, from the late 70’s, retiring in 1989.

For more information on Bernard Byrne click here to go to The Supermariners website.

Alfred John Cook (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Alfred was an Aircraft Riveter at Supermarine. He was 37 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September1940. Alfred is buried in South Stoneham Cemetery, Southampton.

Leslie and Vicky Cooper

Spitfire Maker, Vicky Cooper, interviewed in 2014, shares memories of being caught in the air raid of Woolston, in September 1940. Vicky and hubby Leslie were visiting his parents on St Deny’s Road at the time of the raid.

Click here to listen to Vicky’s interview

Leslie Cooper worked at the Supermarine Works in Woolston. After the works were destroyed and the production of the Spitfire was dispersed he was moved to Trowbridge in Wiltshire. Vicky found herself also having to undertake war work in the factory.

More from the interview with Vicky Cooper – Born 1920. Published with permission………..

“When we went to Trowbridge I had to work in the factory too. I had never worked in a factory in my life….. they had to tell me everything, they had to show me what to do. Of course they called Lesley up, you know, they said they were taking too many men from the Spitfire, I mean the women couldn’t do all the work….all that work, so he was deferred and was pleased.

I’d never held a rivet gun before, they had to show me how to do it. I’d never done anything like that in my life. We had to put things on this metal piece, well I don’t know what it was mind. But anyway, that’s the work I did and, of course, Lesley was a sheet metal worker so he did his work. My friend was worried that we were going to lose the War with me working on the planes.”

Excerpts from “St James’ Park – From Shirley Rec to Renovation – 1907-2014” by Michaela A Lawler-Levene and the FoSJP History Team.

George Edward Copson (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

George was an Engineer at Supermarine. He was 61 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 26th September 1940. George is buried in Hollybrook Cemetery, Southampton.

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Doreen Couper nee Billows – Spitfire Maker & ARP Warden

Doreen’s parents – Her father – Front row far right: Her mother – Front row third from the right

Images courtesy of FoSJP History Group and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Extracts from the transcript of an interview with Doreen in 2012 by Michaela Lawler-Levene – Friends of St James Park History Group – Shirley Heritage Oral History Project………

(Published with permission)

“I was born in St Andrews Road, May the 18th 1924. They had started building a new estate in the Shirley Warren area and from St Andrews Road, I moved to Chestnut Road. My name is Doreen Billows and – we lived at number 30, right opposite the school that was built later which at the age of 13, I attended. That was from Regents Park School – and I left at the age of 14 and went out to work because that was the time that you hd to leave at 14 unless you were in a [pause] Grammar School or the other type of school that you won a scholarship to if you were lucky but most people in those days wanted to go to work because money was not all that forthcoming because you had to pay for doctors and everything. So, that meant that my mother had to work hard in the house and she did sewing and everything else for other people so that we could live an ordinary, practical life which in those days was very, very hard because money-wise things were hard.

My Dad worked as a bus conductor and only earned £2 and 10 shillings. Convert that to what it is now and see what had to happen to your household bills although things were slightly cheaper but we still had to pay for doctors and things like that so you can understand living was very hard.

I left school at 14, as I said, and then went to work and then at the age of 16 the war came about and I had to either go into the Forces or have – a worthwhile job because by the time you were 18 you had to go into the Forces anyway. So I worked at Vickers Armstrong in Winchester Road, just past St James’ Park. Next door was Sunlight Laundry which turned to the components part of Vickers Armstrong and opposite Sewards Garage was the fuselage department where the fuselages were done – for the Spitfire.

My job was the head of the Drawings Library in Winchester Road and I used to go with the drawings from the Library to the component department and Mr Nelson, the head of the whole construction, and Seward Garage with these [pause]

Drawings?

With these drawings, sorry [laughs].

I was secretary to the senior inspector and the [pause] oh dear I’ve forgotten what it was now…… oh dear!….. Foreman of the shop in the Wing Department. I also helped out whith the – wages department, time sheets and tings like that.

I also became at the same time an Air Raid Warden because my Father was a senior inspector. In Warren Avenue there was a brick building built on the square in Warren Avenue and that was the shelter for the wardens to attend to what they were going to do for my father, where they were directed , to either to patrol the roads, look after the air raid shelter and blackouts.

I would go to work in the morning. It would be dark, no lights on at all and even if you had to have a bicycle lamp on your bicycle that was shielded by a shield. And you must go in the morning in the dark and leave at 8 o’clock at night in the dark from work, then go on duty as an Air Raid Warden and then patrol the streets or knock on doors for people showing lights. And then when they dropped bombs seeing, you know, different things what happens and when they put the incendiary bombs down you had to put them out with sand and bucket.

From there, I went to – I went to look after the shelters one night and I can’t remember the time it was but – a bomb hit Shirley Warren school, right on the edge of the school. It hit the shelter full-on, a small shelter, and my father that was the senior warden had had a controversy talk with the Philpotts on the other side where the shelter was to stop them from going into that shelter and coming up to the shelter that I was in charge of, the top of the school, big long shelters. So therefore their luck was in because he wouldn’t allow them to use that shelter and they were up in the shelter that I was in and that shelter got destroyed completely and they would be dead whoever was going over with them because then they would round that lamppost they all wanted to go into there. So in other words my father really saved their lives by doing what he did because he could not spare another warden and as I was in charge of that shelter, when the bomb fell and the ground lifts with you in the shelter you can feel it like. If they’d gone in that shelter they’d have been here no more. From that time, we just, you know, carried on as we were.

You’re up and down. I had to go outside and find the damage that was done so I had to tell a lie [laughs] because when I went out there was glass all over the steps, all the tiles were blown off the roofs, glass all down the road and tiles. So I went back and they said “ohh, what happened?” And I said “not much really” [laughs] so had to just, you know, leave it at that. But of course they found out when they went out. Well, my father was profusely thanked by the people that were going to use that shelter they couldn’t because we just did not have the wardens to keep all these shelter open. So in other words, it was a good thing because of they’d been in that shelter they’d have been here no more. From that time, we just, you know, carried on as we were.

I used to go to work at 8 o’clock in the morning to half-past 8 at night then cycle home in the dark and start cycling home during the winter in the dark. No lights at all were on, nobody was allowed to see a light anywhere and all you had was just two instants to go where you were going.

Course we had a little bit of laughter and fun when we used to go dancing and that sometimes – without the sirens we hoped [laughs]. And we’d go to cinemas: there was the Regents at the top of Shirley, the Rialto and the Atherley next to each other at the middle of Shirley.

In time the Children’s Hospital was knocked down and they put flats and houses there and the clinic was just as short-lived because I think they turned that into flats, it’s the flats there now. But all along the sides of St James Park area, there are – St James Church and alongside of that, until they built the clinic up, there were these big houses and they were really big and with their own grounds but they were in time knocked down most of them. St James Church is still there and still going strong. I was married there [laughs] in 1948 so things were different then though.

And then of course during the war, I worked up further in that area in Hants and Dorset – which was the old bus station, for charabancs, as they were called then, now called coaches. And , they would do all the mending of all the engines and things, you know, inside the coaches and that. And that was the part that I worked in so I knew all of that area beforehand.”

Would you mind just mentioning what sort of work you did there again, just briefly?

“Well, when I was at Vivkers Armstrong, Hants and Dorset Bus Station, I worked – I started at 16 years old, I was head of the Drawings Library, secretary to the foreman of the shop and the senior inspector and – I used to do a lot of running about from one place to another. From Hendy’s, the fuselage department and Sunlight Laundry, the components department and Mr Nelson, whose house was alongside Hendy’d garage, I used to go to his department and – he was – it was just him and his secretary in that house and he was invovled in all that area of Vickers Armstrong so – in 19…. I think it was 1942. they had women = they had women into Vickers Armstrong, the wing area, and they helped build the wings. These were the first women in this area to come into the – the wing department.

I have got a question to ask you. When you used to go up to Hants and Dorset…….

“To work.”

To work, do you remember seeing the activity in the Park, the barrage balloon and that then?

“No, not really because it was dark most of the time, you see. Dark in the mornings because you used to sometimes be cycling up there half past seven. And then during the summer, you didn’t sort of look around, you just went on now on your bike [laughs] and then coming home was nearly always dark because if was half past eight so you didn’t see, you know, and you worked – I worked……I was lucky enough to work five days a week and like a Saturday morning sometimes. If they asked you to work on, you would do it. But from – when you think of it, a sixteen year old girl, working from 8 o’clock until half past 8 at night, it’s not funny is it?”

Excerpts from “St James’ Park – From Shirley Rec to Renovation – 1907-2014” by Michaela A Lawler-Levene and the FoSJP History Team.

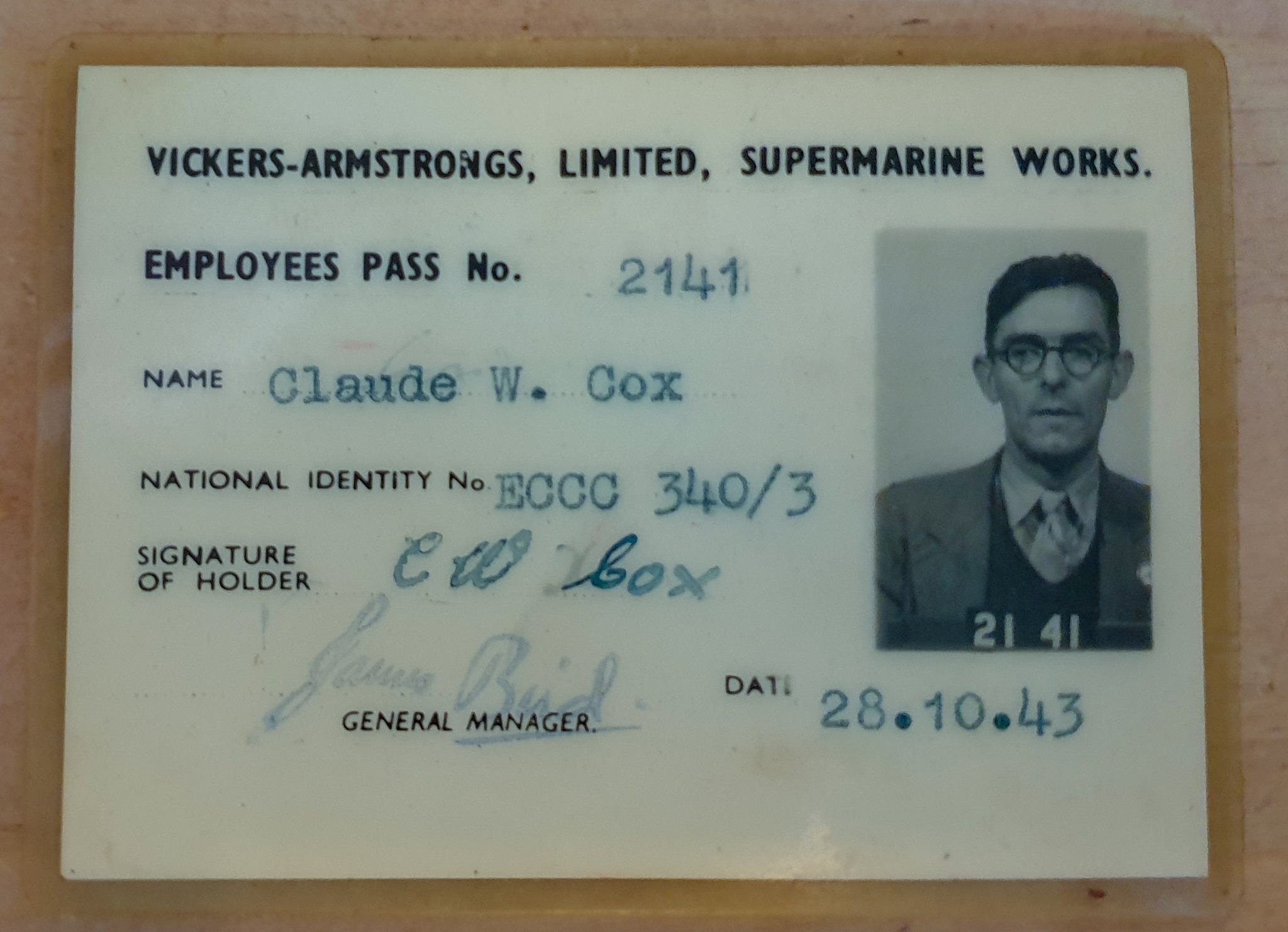

Claude Cox 1916 – 1989

Images courtesy of Glenys and Trevor May and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Recently, Dave Key of The Supermariners project and Spitfire Makers chair, Alan Matlock, met with Glenys and Trevor May and heard about Glenys’ father, Claude Cox, who lived in Woolston and worked for Supermarine from the 1930s.

We would like to thank Glenys and Trevor for sharing Claude’s Spitfire-making story.

Claude Cox 1916-1989

Claude started work as a Supermarine riveter before WWII. A rescuer noticed a hand sticking out of the rubble after the bombing in September 1940 and Claude was pulled out alive.

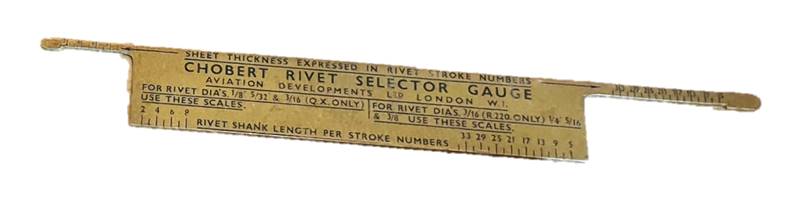

He continued working for the company after the war, returning to Woolston to work on early hovercraft and also working for Thorneycrofts. Some of his tools are shown here.

Comment by HM on Facebook – It’s been a very long time since I last thought of ‘chobert’ blind rivets, let alone the tools for installing them. Happy days I guess.

Comment by Spitfire Makers on Facebook – it would be great if you could explain what these tools were for and how they were used…

Comment by HM on Facebook – The yellow gauge is for selecting the correct length. The apparatus that resembles pop rivet pliers draws a mandrel through the rivet to expand it in the assembled structure. The next stage is to insert a sealing pin, a small dural slug that is an interference fit. The rivets come loaded in sticks held in place by a paper wrapping. The rivets are loaded onto the mandrel which is then loaded into the pliers. I’ve not a clue about the third item, sorry. I hope you find this useful, like I said it’s a long long time since I used them. For its time it was very much like the pop rivet but better. Cheers

Leonard Herbert Cox (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Leonard was an Aeronautical Draughtsman at Supermarine. He was 20 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on 24th September 1940. Leonard is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

Douglas Cruikshank (d. Sept 1940)

Images courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Douglas was a “Shop Boy” at Supermarine. He was 14 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on 24th September 1940. Douglas is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

James Curtis (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

James was an Assistant Progress Clerk at Supermarine. He was 41 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 26th September 1940. James is buried in Hollybrook Cemetery, Southampton.