- Vera Saxby nee Hayward

- Jane Sheriff

- Beatrice Shilling

- Walter James Shiner (d. Sept 1940)

- Don Smith

- Ellen (Nell) Smith nee Sennett

- Roy Geoffrey Staples

- Dennis and Betty Stephens

- Leslie Herbert Stone (d. Sept 1940)

- Charles Frederick Strugnell (d. Sept 1940)

- Philip James John Thorne (d. Sept 1940)

- Henry Godfrey Thwaites (d. Sept 1940)

- Frederick George William Turner

Vera Saxby nee Hayward

Vera Hayward, pictured here in 1945 and also in March 2023 at the unveiling of the Autometalcraft plaque, was secretary to the Works Manager, Ben Curtis.

Jane Sheriff

Jane Sheriff in the late 1930’s. Image courtesy of Judy Theobald

Jane was one the first female Progress Chasers for Supermarine during the war. These are her memories of that time with annotations by her daughter Judy Theobald…………..

Having got engaged on Christmas Day, 1935, my parents, Alec and Jane Sherriff, were married on 21 June, 1937, in St James’ Church, Shirley. They spent their honeymoon in Scotland.

Jane: ‘I enjoyed my honeymoon, but I couldn’t wait get back to my lovely new home at 181, King George’s Avenue, Millbrook (now Regent’s Park). It was a six-room, semi-detached house. We took out a mortgage with the Halifax Building Society and paid eighteen and four pence a week, paid monthly over a period of 21 years. However, we so wanted to own our own home that we ploughed back as much as we could spare and finished paying for it in 15 years. (September 1950 according to the building society book, so even less time.)

By careful saving during our engagement we were able to buy carpets and linos, basic furniture and a gas cooker outright, and started married life with £60 in the Post Office and no debts. Alec’s weekly wage when we first married was £3.7s.6d (£3.37.5p) which rose to £3.15s (£3.75p)- soon after.

Our house was one of several, newly built on the edge of the town. The back overlooked allotments and beyond that there were farms stretching almost to the New Forest. One of the delights of our house was the fact that there was a strip of land at the bottom of the garden running along the backs of the houses which could not be built on as the stream which ran through it, Tanners Brook, sometimes flooded in winter. Each house was therefore offered an allotment which suited Alec very well and he kept us in fresh vegetables throughout the year.

Our house was typical of the period, three bedrooms and semi-detached. There was a back boiler behind the grate in the dining room and later on we had an immersion heater installed for hot water during the summer months. The only kitchen aid I had when we first married was a gas boiler which was included in the price of the house (This was made of copper and just known as ‘the copper’. It was used for washing clothes. It was free-standing; you pulled it into the middle of the kitchen, filled it with water and lit a naked flame underneath). There was a larder but no fridge of course, no washing machine, no food mixer and no pressure cooker. I did have a carpet sweeper and a Goblin vacuum cleaner.

Alec’s sister Mag and husband Edgar (who owned an ironmonger’s shop in Ringwood) gave us all our cutlery as a wedding present and sold us all the kitchen equipment we needed at cost price which was a tremendous help. There was no plastic kitchenware and my working surface was a white wood table which had to be scrubbed frequently as did the wooden draining board. The only other furniture in the kitchen was a glass-fronted dresser where I kept the dinner service on display, and some open shelves.

There was an outside lavatory and one upstairs in the bathroom at the front of the house.

The War

Between the time of the outbreak of war and Alec’s call-up, he had to take his turn at fire watching at the Echo Office (this was situated round about where the Above Bar Street entrance to West Quay shopping centre now stands). He did not like leaving me in the house so on these nights I went to the public shelters under Regent’s Park School and Alec would collect me on his way home. Came the day when we came home to find a hole in our roof, and our bed a mass of rubble. It was not a bomb but blast from a bomb which landed in the garden two doors away.

(Both my parents told me the story of the big raid on Southampton on the night of 30 November/1 December 1940. Dad was on firewatch so had left mum at the Regent’s Park School shelter and then cycled into town. The raid started fairly early on with the Luftwaffe taking out the water mains first and then dropping incendiary bombs. He and an air-raid warden standing in the high street were only able to watch as there was no water to extinguish the flames. He did manage to save the Echo sports and social club by using fire extinguishers. In the meantime, mum said people kept coming into the shelter saying, ‘Boots has gone,’ ‘Timothy Whites has gone’, and she didn’t dare ask if the Echo had been bombed as that could have meant her husband had been killed. The shelter also took a hit. It wasn’t destroyed but it tipped sideways and mum used to tell me about the woman air-raid warden who was in there with them and who didn’t bat an eyelid when this happened and then mum would cry.)

There was an army of men on stand-by to work quickly to do emergency repairs and we soon had a weatherproof home again. Then, when the raids become more severe, Mag and Edgar offered to store our furniture in their storerooms as they could not get the stock to fill them. When we were loading our furniture into a van, some people who had been bombed out from the centre of the town asked if we would rent them our house for duration, and we were only too glad to have some money to keep the mortgage going. We didn’t want to make any money out of them, just enough to cover our expenses. Then we went down and stayed with Mag and Edgar to have a break from the bombing for six weeks. (I think this was after the major air raid on Southampton as dad’s address on the reward letter is shown as being in Ringwood. Two other family members went down. One of them was my uncle who had been wounded on the Somme in the First World War and was also wounded in the big air raid of November/December, 1940. This had a severe effect on his mental health and he was never quite the same again. My late cousin Jim remembered them all arriving, uncle with his eye bandaged and my father covered in soot from where he had been trying to extinguish the fires. On a lighter note, I remember mum telling me she got quite fed up with eating pheasant because being close to the countryside, that was one thing in plentiful supply.)

By then my father had been called up and in February, 1941, started his army training.

When Alec was called up I went to stay with my parents in Maybush where I had a bed in the corner of their lounge. My parents were very good to me and charged me very little for my board and lodging. The army also paid me a small allowance and Alec sometimes sent me some money from his allowance as he had no opportunity to spend whilst fighting in the desert. By the end of the war I was able to show Alec a deposit book with over £1,000 to our credit. Some of this went into a building society and I found the interest a great help with the children’s clothes.

As soon as Alec was called up I volunteered to work in a Spitfire factory. Had I not volunteered I should have been drafted into the forces and probably been sent abroad and not seen Alec again until the end of the war. Bob Broughton, my friend Gretchen’s husband, introduced me to the foreman of the factory and I was taken on right away. The factory was a unit of Vickers Armstrong in a commandeered laundry in Winchester Road. (This was the Sunlight Laundry and the site of where Wickes now stands.) I started as a drawings librarian and sometimes stood in as a telephonist on a small switchboard. Then I did some time in the time office.

Then the progress chasers were being called up. All of them were men and the Air Ministry said they should give the jobs to women. There was an outcry. It was no job for a woman. They will never grasp the technicalities!!!! They will have to put up with the bad language from the men on the bench, etc. But the Air Minister was adamant so a girl who was stationed over the road at Sewards Garage and I were the first two women progress chasers to prove that women could do the job. We were such a rarity that I had a man in my office on day who said he didn’t want anything but to see what a female progress chaser looked like. What cheek!

(Despite the concerns over ‘bad language’, there was some effort to curb this. During the war, Southalls made sanitary towels and when mum was in a meeting once, someone said a particular component was available from Southall. One of the men then said, ‘That’s not the only thing you can get at Southall,’ and was severely reprimanded for saying such a vulgar thing in front of a woman)

Anne Summers was assigned to the fuselage shop and I stayed in sub-assemblies. As production was stepped up I was given help. Freddie Brown, who had been invalided from the RAF after two horrific accidents came to help me. He was a delightful man with a daughter aged five at that time. Later they had another girl and they named her Jane after me. After that they had a son. Freddie and I worked very well together and had a good brother and sister relationship. We are still in touch today.

Later on, in 1944, when things began to ease off a little, modification took priority and I was sent to the unit at Hendy’s Garage in Chandlers Ford where I stayed until the end of the war.

Our factory hours were very long for the first three years – 7.30am to 7.30pm, Monday to Friday, 7.30am to 4pm on Saturday and 7.30am to 3pm on Sundays. Often we couldn’t get a good night’s sleep owing to the bombing. I became so desperate for sleep that I didn’t get up when the sirens sounded but took a chance and stayed in bed.

(Mum used to cycle to work, both to Winchester Road and Chandlers Ford though I think she had a driver when she was at work because she had to travel around to all the other shadow factories making sure all the work was co-ordinated. In the winter months, the air raids had often started while she was cycling home and in the mornings she’d have to make her way round bomb sites to get to work.)

When the siren went at night my parents put overcoats over their night clothes and went into the Anderson shelter dug into the garden. Mother went armed with the deed box containing anything that could be of the slightest use, together with a basket of biscuits and a flask of coffee. The dog was so used to this routine that as soon as the siren went, he was out of his basket, waiting to be let out of the door and he was the first down the shelter. It could be very cold in the shelter and some heat was gained by wedging a candle into the bottom of a flower-pot and placing another flower pot on top to form a kind of lantern. The earthenware generated a surprising amount of heat. There were two bunks on either side of the shelter and just enough space in the middle to get in and an orange box at the end to hold the candle.

(My mother’s brother suffered from severe asthma all his life and was medically unfit for service. He worked as a cartographer based at the Ordnance Survey in Romsey Road, close to where they lived. He did take part in fire watch during the war. He died of cardiac asthma in January, 1954)

When Alec was demobbed in February, 1946, by which time I was pregnant with Janet, we expected to get our house back as arranged but the tenants would not move out and we had to take them to court. (Because of the post-war housing shortage, it was necessary for homeowners to prove they needed their home more than their tenants). Happily, we won the case and in April, when I came out of the nursing home (pre-NHS) with Janet. I was able to take her straight back to our own home instead of my parents.

Our house was in a dreadful state, so very dirty. Our new gas cooker we left for them as theirs had been lost in the bombing, was coated with burned-on grease. I don’t think they had cleaned it once in all the five years they had it. Alec used to sit on the back doorstep, chipping away at the grease. It was heart-breaking. We had workmen in to decorate right through the house. They could see how badly our tenants had left it and were very sorry. One of the workmen happened to be an old friend of father’s so did more for us than he was obliged to.

As well as working long hours, my mother said if there was more work to do, she would stay all night, doing 24 hours non-stop. After the war, my father was very proud of her because she knew every part of a Spitfire. She always said she could have built one from scratch!

We were talking in the group about normal life also continuing during the war. I have the Halifax Building Society book which my parents used to pay the mortgage. This was paid in cash over the counter and the amount entered in the little book. There is a gap for the payment due at the end of November, 1940, so it’s possible the premises no longer existed at that point. However, double the amount was paid the following month so everything must have been up and running by then.

A very sad story my mother told me about the war concerned her best friend, Doris Stevenson. Doris was married and had a small baby and they lived close to the centre of Southampton. When the bombing became severe, the three of them rented a bedroom from someone living on the outskirts of Southampton; they would spend the days in their own homes and the nights in the rented bedrooms. However, people capitalised on the fears of those living close to the danger and charged them extortionate rents. In the end, Doris and her family could no longer afford the rent and had to go back to sleeping in their own home. The three of them were killed by blast from a bomb which dropped nearby. Apparently, there wasn’t a single mark on them but they were all dead. Mum cried about that whenever she mentioned it, right up to the end of her life. I always thought the people who charged the extortionate rent were as guilty of their deaths as the Germans were.

Beatrice Shilling

The People’s Spitfire : “The Shilling factor”

Episode 6 of 10 – A wonderful series available on BBC Sounds, and available as a podcast. As brilliant as the Spitfire was, it had one major flaw : in a steep dive fuel couldn’t reach the engine, and the engine choked. A solution is urgently needed. That was a job for the fastest woman in Britain: champion motorcycle racer and pioneering engineer, Beatrice Shilling – in her own way another of our Spitfire Makers! https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w13xtv79/episodes/downloads

For more information on Beatrice Shilling click here to go to The University of Manchester’s website.

Walter James Shiner (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Walter was employed at Supermarine in an unknown role. He was 30 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 26th September 1940. Walter is buried in South Stoneham Cemetery, Southampton.

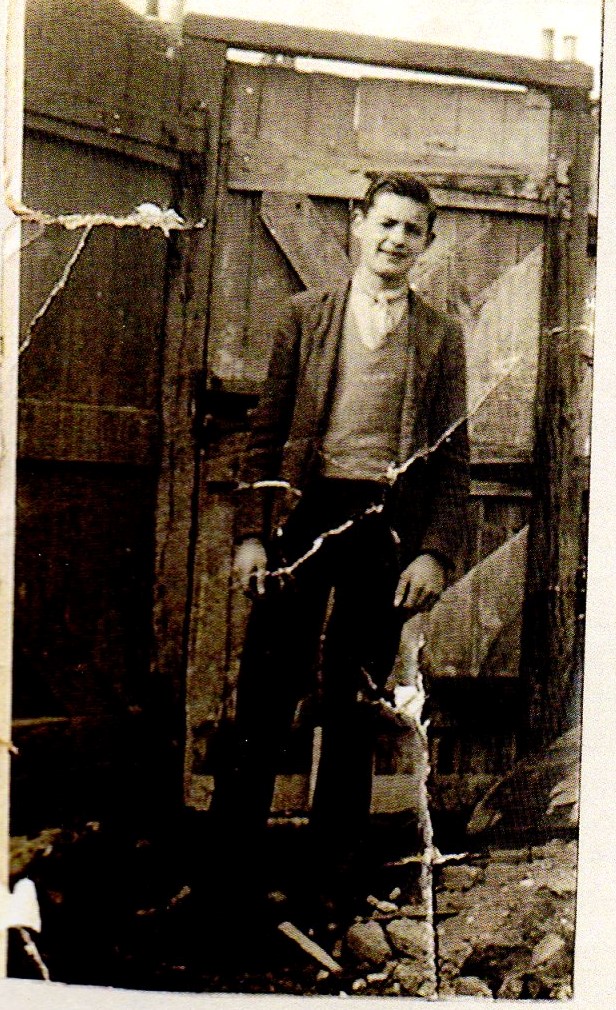

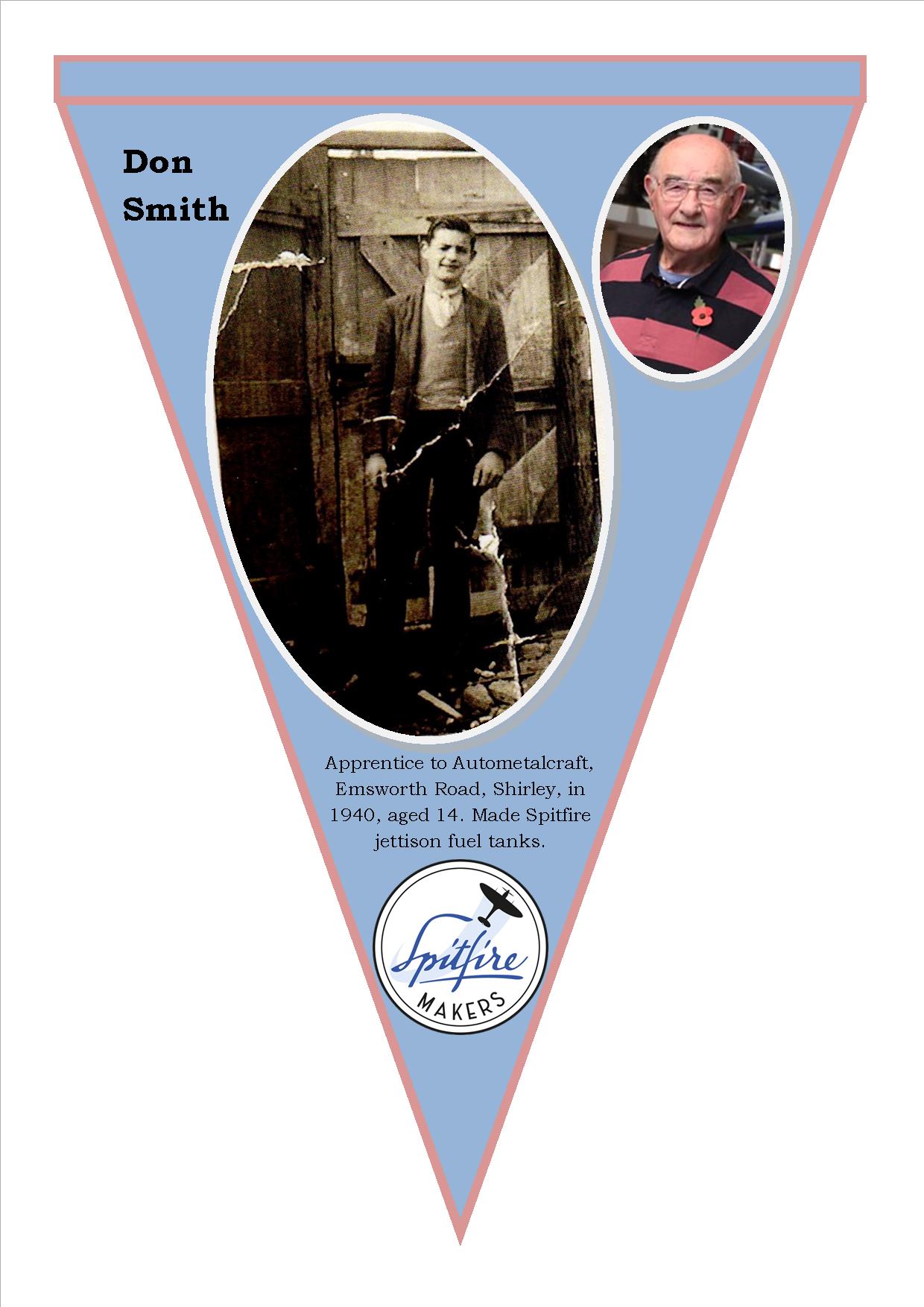

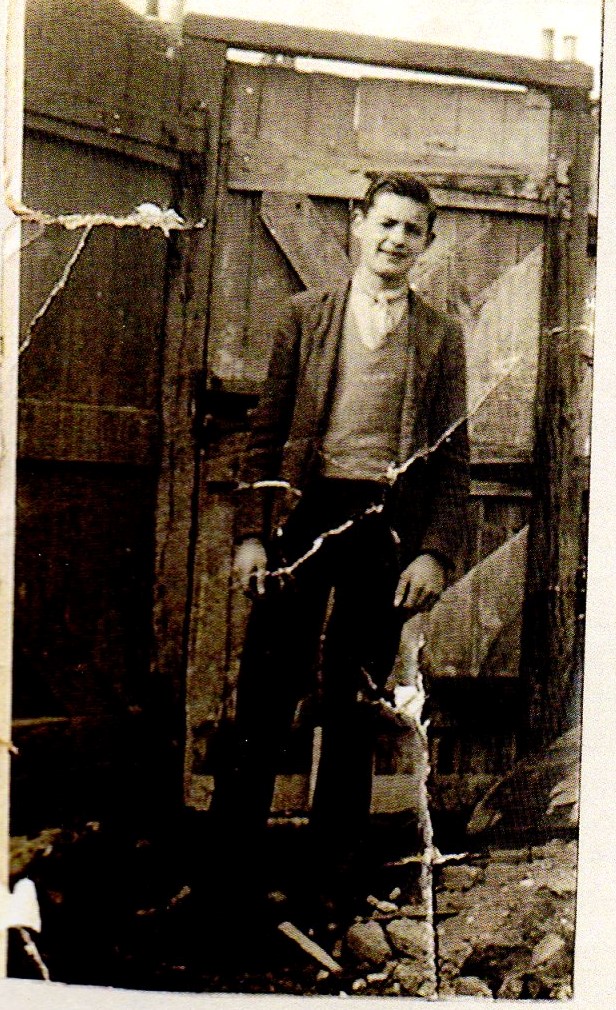

Don Smith

Images courtesy of the Smith family and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Don left school at aged 14 at the outbreak of WW2. He recalled that his school, Foundry Lane , was taken over by Canadian Troops at that time. He went to work as an apprentice at Auto Metalcraft in a building just off Emsworth Road in Shirley, Southampton. The building is still standing as part of the Emsworth Road Industrial Estate.

Autometalcraft specialised in car body repair work and the men working there, including Don, were very skilled in making the parts needed for the repairs as “spare parts” were not available as they are today. These skills were recognised by Supermarine when they were looking to “disperse” the Spitfire production following the bombing of the factory buildings in 1940.

Download the notes of a conversation with Don by our Project Team member Vicki in 2020

Don returned to the Emsworth Road site for a visit in December 2020. Click here to read about the visit.

In 2020 we were honoured that Don

Posted on Facebook by Michaela Lawler-Levene in May 2020

Spitfire Maker, Don Smith, receives a VE Day afternoon tea and gift pack from Shirley Local History Group and Friends of St James’ Park. During WW2 Don made Jettison Fuel Tanks at Auto Metalcraft, in Emsworth Road, Shirley. The site of the Spitfire Makers factory is now home to the Masker’s Theatre. Before lockdown Don was invited to go and speak to the members of the theatre about their building during WW2. All on hold for now. We all send our best wishes to Don.

Just the ticket for Spitfire Maker Don!

Hon President Don Smith went back in time to his days as a wartime Apprentice Spitfire Maker and Tram Conductor when he visited Solent Sky Museum in Southampton. Don spent the morning at the museum and presented Solent Sky director Alan Jones with some original tram tickets.

After he left school, Don worked for Supermarine subcontractor Auto Metalcraft in Emsworth Road, Shirley, Southampton and then went on to work as a conductor and trainee driver on the Southampton trams. He also served in the Home Guard and the bayonet he never handed in at the end of the war will now have a home at the Museum. In front of the Solent Sky Mark 24 Spitfire Don was able to hold a Spitfire air intake, one of the same parts he used to make, for the first time in 80 years. This was one of several items loaned to the museum, specifically for Don’s visit, by Southampton-based aircraft parts maker Mark Cole who produces airworthy replica parts for Spitfire restorations.

During his visit Don was presented with a Spitfire Makers lapel badge which reminded him of the only other Spitfire badge he had had which was made by one of the workers at Auto Metalcraft out of an old halfpenny coin.

A film of Don recounting his many stories of those far-off days will be available very soon and the Museum is now open again for visitors after the latest lockdown – https://www.solentsky.org/

Solent Sky Museum Photos: Infinity Photography by Sarah Penfold and members of the Spitfire Makers project team.

Images by Sarah Penfold and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust members

How to make Spitfire jettison fuel tanks

Our Honorary President Don Smith, filmed at Solent Sky Museum, talking to Spitfire Makers chair Alan Matlock about his very clear memories of working for Supermarine subcontractor Auto Metalcraft in Emsworth Road, Shirley, Southampton.

Thanks to museum chief executive and curator, Squadron Leader Alan Jones for his kind invitation and John Beck for his excellent camera work: john@beckfilms.co.uk

Listen to the interview here or view the video on our Facebook page:

History in his hands…

Don Smith, Spitfire Makers’ Honorary President, proudly holds a commemorative plaque destined for the building which, as a 14 year old apprentice, he helped prepare for the production of Spitfire parts.

The cast aluminium plaque, made by Leander Fabrications, arrived in Southampton today and it was fitting that Don was the one to unpack it and the first to see it.

Spitfire Makers have identified the location of over 30 Spitfire production sites across Southampton and many more beyond.

If you would like more information about these and how you can sponsor a plaque please go to www.spitfiremakers.org.uk

RIP “Smiffy”

It was with great sadness that we announced the death of our Spitfire Makers Honorary President, Don Smith in February 2023

Don first came to the attention of the Shirley Local History Group about 15 years ago when they were researching the history of the Shirley Rec’, now St James’ Park. Several members of that group are now part of the Spitfire Makers project team.

From the age of just 13, with almost all his schoolmates having been evacuated, Don went to work for Auto Metalcraft Ltd, just across the road from his childhood home in Shirley – see photo below. There he helped turn 6 foot long sheets of high grade aluminium into Spitfire jettison fuel tanks and air filters.

When production of these parts needed to be expanded he was taken to help with the installation of gas pipes into what is now Shirley Parish Hall. Fittingly, this is where, in March last year, Don helped to unveil the first of the Spitfire Makers blue plaques. Sections of Don’s pipes can still be seen in the Hall.

For the unveiling of our next plaque – at Auto Metalcraft’s premises in Emsworth Road, Shirley, (now home to The Maskers Theatre) on March 4th we would have loved to have had Don with us. (See previous post for info about this event.) He advised us on the wording for the plaque and on March 4th we will especially be remembering him and the contribution he and so many of the unsung Spitfire Makers like him made.

Don’s stories of his apprenticeship at Auto Metalcraft are precious records of how even young teenagers were helping the war effort in those dark days.

During one of the many air raids, an Auto Metalcraft lorry had apparently run out of fuel on the Avenue. With the air raid still going on, it was Don who was sent to cycle across town – with a bucket of petrol hooked on his handlebars – only to find it was the lorry’s brakes that had seized!

He tells too of the night-time air raid when his grandmother, who lived with them, had to be coaxed out of bed to the family Anderson shelter (still standing in the garden at the back of Shirley High Street). To provide them some protection from the shrapnel falling from above, Don picked up the lid of the metal dustbin. It was only in the morning he saw a jagged piece of metal had embedded itself into the lid!

Don went on to work at Solent Carpets who were making parts for wings and pilots’ seats. He was a tram conductor and trainee driver and in the Home Guard before he then joined the Army. After the war he worked for many years at Hampshire Car Bodies (another of Supermarine’s wartime subcontractors) which later became HCB Angus.

He was always so generous with his time and, with stories such as these and many more, a great source of information for our project. He was delighted, as were we, for him to be our Honorary President. He was a proud Sotonian and a true gentleman.

RIP ‘Smiffy’

Images courtesy of the Smith Family, and Spitfire Makers

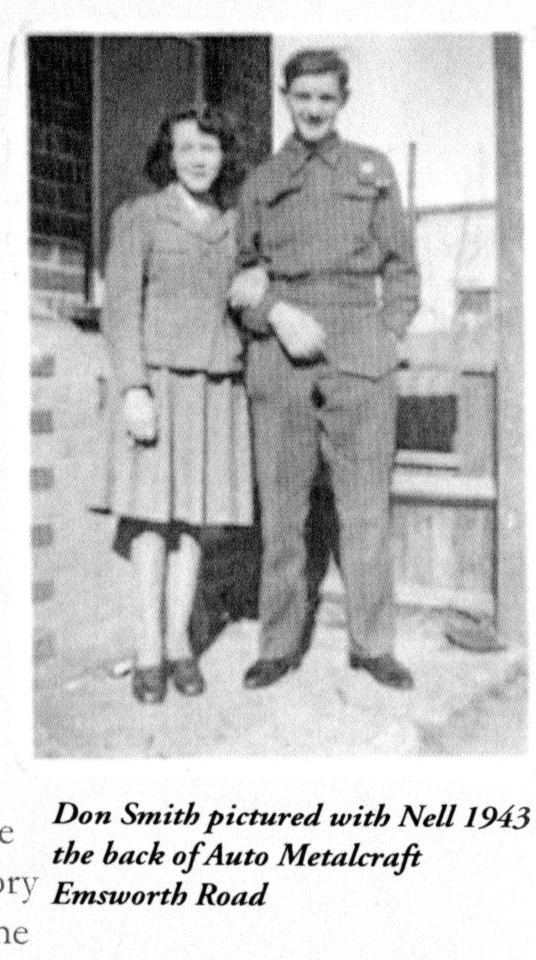

Ellen (Nell) Smith nee Sennett

The Autometalcraft Ladies – Pat Pruce, Lily ?, Nell Smith

Images courtesy of the Smith family

Many women were trained to work for subcontractors like Auto Metalcraft in Shirley. Nell met Don Smith there, making Spitfire fuel tanks and air filters. Both went on to work at Solent Carpets who produced waterproofing for amphibious tanks, jerry cans, blankets and bomb-release mechanisms as well as shaped pilots seats and aluminium ribs for wings.

Roy Geoffrey Staples

Roy & Eileen Staples c1934 – Images courtesy of Colin Staples

From his son Colin Staples…….

Here are a few facts (There are a number of questions I would have liked to ask my father but that’s wisdom of hindsight)

Roy Geoffrey Staples DOB 12 10 1911

His address was 7 floating bridge Road lived above shop and bakery obtained private pilot licence including one crash landing in 8 hours at Eastleigh airport.

When Floating Bridge Road was bombed before Supermarine billeted him near Sarisibury green adjacent to ATC site today.

Told to go to work at Woolston Supermarine and allocated to be a tool make as he knew trigonometry and could interpret drawings.

Escape injury when Supermarine was bombed for the second time as with a few friends he spent the warning period on a small boat in the Itchen.

Was moved to several locations mainly worked nights and travelled on his Velocette motor cycle including Hursley.

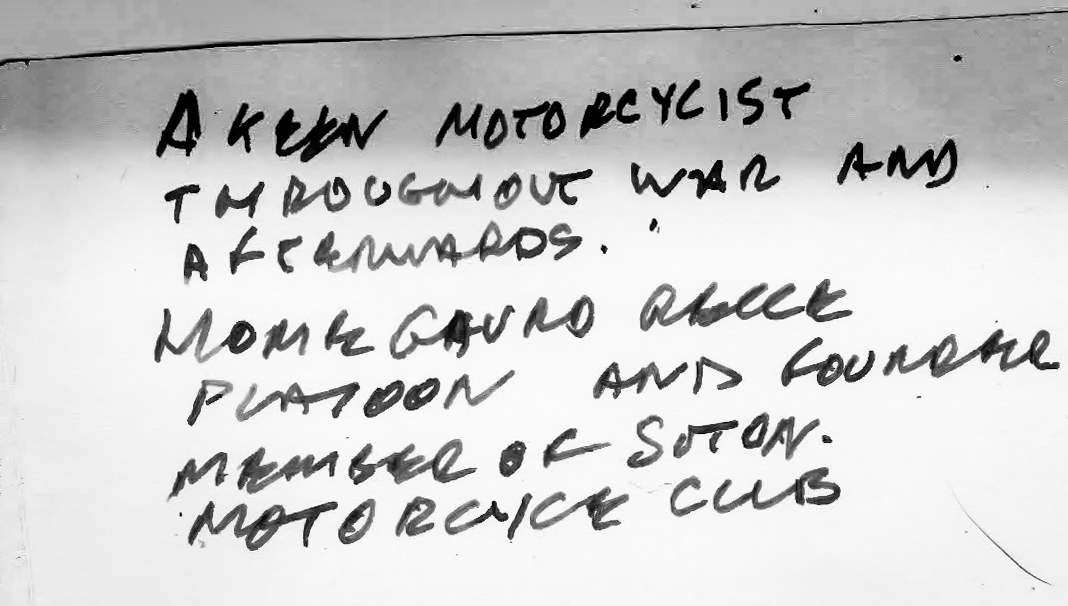

Joined the home guard reconnaissance platoon with his bike and became a founder member of Southampton Motorcycle club which emerged from the Home Guard Platoon.

I have benefitted over the years from his experience of a very wide number of engineering and practical skills.

As Churchill said, he could not understand how you could train a Spitfire pilot to die for his country in a few hours but it took so long to train for a trade. Spitfire manufacture was a good example of deskilling and enabling key skills to be obtained in short time a classic example of value analysis!

Dennis and Betty Stephens

Image courtesy of Quentin Hurst

From their grandson Quentin Hurst……….

Dennis Stephens and his wife Betty both worked for Supermarine in Woolston. Dennis had enlisted with the Royal Artillery but, because of his experience, was sent back to Southampton.

They got married in uniform and it was “the first khaki wedding in Portsmouth”.

Betty worked in the canteen and Dennis received this certificate to recognise his contribution in March, 2006.

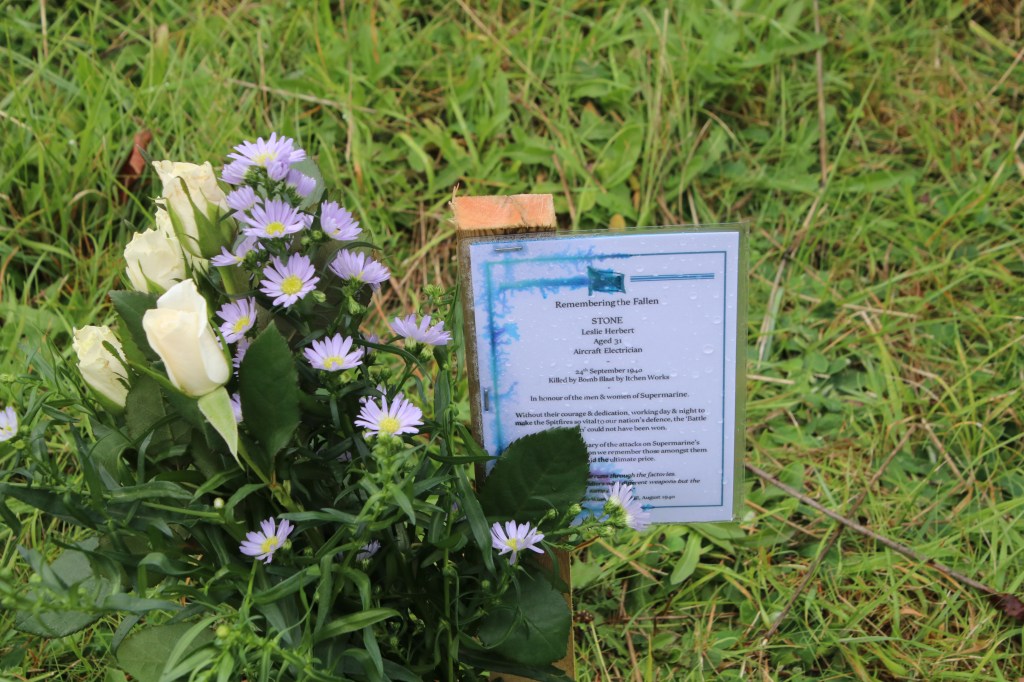

Leslie Herbert Stone (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Leslie was an Aircraft Electrician at Supermarine. He was 31 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. Leslie is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

Charles Frederick Strugnell (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Charles was employed at Supermarine in an unknown role. He was 59 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. Charles is buried in St Mary Extra Cemetery, Southampton.

Philip James John Thorne (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of Stuart Thorne

From his grandson Stuart Thorne……..

“Philip James John Thorne was a riveter and died in the Sept 1940 bombings. He had made it through the railway tunnel to the shelters at the bottom of Peartree Green and was either at the entrance to the shelter or just outside when the bomb dropped.

Apparently he had gone home for lunch, in Deacon Road, Bitterne, and then left on his bike to go back to work. He told his mother Millie, “Save me some of those tomatoes”….he never came home.

Sadly, the temporary morgue for casualties was set up in the hall at Itchen Grammar School, just behind the family home.”

Philip was aged 35 when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. As we have been unable to locate Philip’s grave, floral tributes for him have been placed on the Commonwealth War Graves Memorial in Hollybrook Cemetery, Southampton.

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Henry Godfrey Thwaites (d. Sept 1940)

Image courtesy of The Supermariners and The Spitfire Makers Charitable Trust

Henry was employed by Supermarine in an unknown role. He was 50 years of age when he was killed in the bombing raid on the 24th September 1940. As we have been unable to locate Henry’s grave, floral tributes have been laid for him on the Commonwealth War Graves Memorial in Hollybrook Cemetery, Southampton.

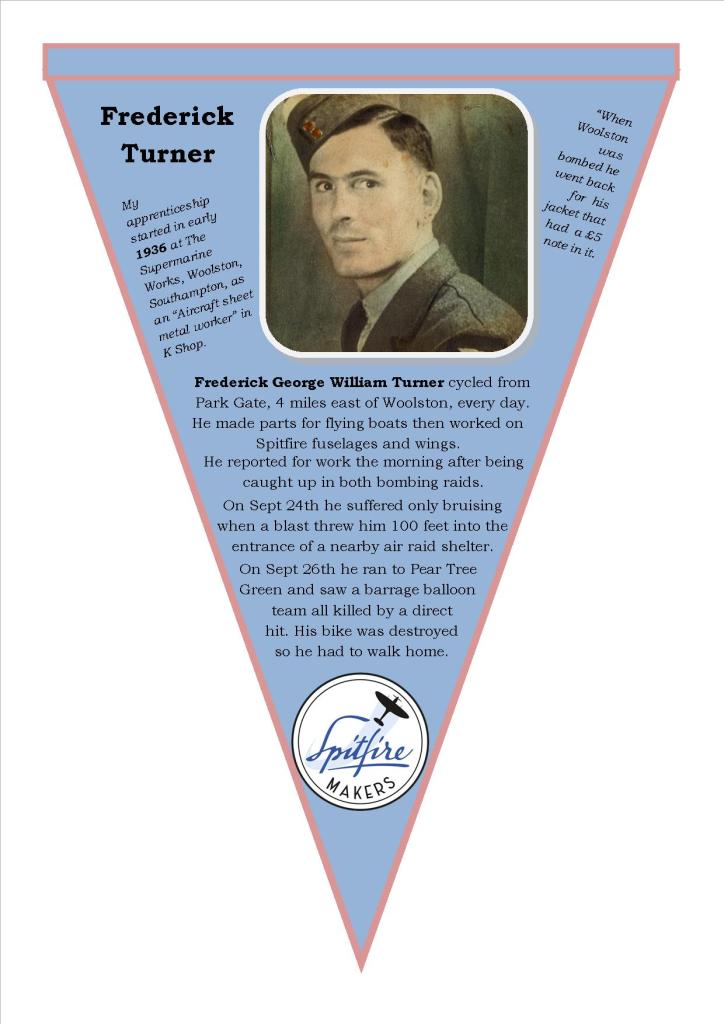

Frederick George William Turner

From his son……

These were the war time memories of my father Mr Frederick George William Turner 1920-1991 who recalled these memories in the 1980’s

He bravely served King and Country in the production of SPITFIRES during world two at the Supermarine Factory Woolston Hants.

1st Production of Spitfire & Bombing of Factory

“My apprenticeship started in early 1936 at The Supermarine Works, Woolston, Southampton, as an “Aircraft sheet metal worker” in K Shop. My salary for the first YEAR was 9 shillings and 9 pence, (just under 50p a week). On the 4th year of my apprenticeship, the year before I became a skilled man, it had risen to 27 shillings and 6 pence or £1.75p, in today’s money, per week. The base wage was very low but if you did a fair days work, which was recorded hourly, you could earn much more with a bonus output. The quicker you were at your job the more you earned. If you did not make your bonus you were in trouble if the last person to do that particular job you were doing made a bonus on it. So there was also a sharp eye on your daily work and a warning if you did not toe the line.

We apprentices would work with skilled men on assembly of the hull of the “Southampton” flying boats and we built the “Walrus” an amphibian coastal command flying boat. They were both bi-planes. The “Southampton” was a twin engine and the “Walrus” was a single engine “posher” type. In our workshop there were several jigs to build the “Walrus” hulls and 2 bigger jigs to build the “ Southampton” flying boats, the rest of the shop was scattered with benches and all the equipment to make component parts most of which were made by hand.

Our working hours were from 7.30am to 5.00pm and the week included Saturday morning from 7.30am to 12.00pm (a 48 hr week). On the commencement of work your coats, which were hung on a triangular coat rack and attached to wires were wound up to the roof, 80 feet up and stayed there until lunch time and then again until the day had finished.

Talking away from your work was quickly broken up after a few minutes by the supervisor. But these sort of conditions were accepted by everyone also the few hours notice that you could get for bad workmanship, lateness etc. We apprentices who lived out of the area, that being 4 or 5 of us, who lived in the Park Gate area 4 miles away, would leave home at 6.45am, meet on the road and cycle together to Weston in all weathers. Snow, ice the lot. If you got wet we worked in it until we dried out. In winter this was a common thing, there was no such thing as being late. On the 3rd minute after 7.30am the factory gates were closed. This is to give you an insight of what one type of working life for a young engineering apprentice was like.”

The Leading up to and the Wartime Experiences

“I will now start to retell, as in my eyes……..It is a part of the History of our Little Island.”

“In 1939 in our K workshop was erected at least a dozen jigs and being builders of flying boats to us they looked like large float jigs for a very big flying boat, but we were soon told they were fighter plane fuselage jigs.

We were then told “SPITFIRES” the latest fighter for the RAF. This to us was very a new experience and quite a challenge compared to the much larger flying boat fuselages. Very quickly the skilled men and the older lads were given a young apprentice or a “Handy Lad” ( as the non-apprentices were called) as a mate and started the assembly. This meant fitting the frame work to the jig and then assembling shaped wings over the frame work. This entailed a lot of work, which I shall not go into but could, before the skins were put back. Finally for the riveting squads. A Riveter and “Holder Up” made a squad.

Within a few months the “SPITFIRE” fuselages were being taken out of the jigs and placed on cradles in the shop for further work, such as cock pits and tail units. Then transferred to a newly built hanger and workshop just a ¼ mile up the road to the river to where our factory was. This was called “The Itchen Works”. There the fuselage were complete, less the wings and sent to Eastleigh for the wings and test flight.

Once the new Itchen Works was fully established, we and the “SPITFIRE” fuselage jigs were transferred there. This put us all under the same roof, so as soon as the fuselage was complete it was on the cradles and placed on the production line. There were several lines arranged in the shop or hanger as it could be called. In any one time there would be 20 or 30 “SPITFIRES” at different stages up to tails, cockpits & engine fitted ready for transport on low loaders, which we called “Queen Marys”. They were designed to carry the aircraft complete with wings if necessary.

It was now 1939 and war was declared against Germany. This put a different light on us as we were a main target for German bombers. Knowing that there were bases just across the channel and we could be bombed at short notice any time of the day or night made a VERY uncomfortable situation for us. It was then we had installed a warning system that applied to us only. If this warning went we had approx. 2 mins to evacuate the place and we were to ignore the town sirens ( which went off quite often) and carry on working. But at each time the town sirens went we would wonder it the “Bombers” were heading for us, knowing that it would happen and soon.

This continued for a few weeks then on a Tuesday morning, I’m not sure of the date (24th Sept 1940 – researched) the outside sirens sounded as usual but this time our own sirens blasted out and red lights flashed on and off.

They were here! We dropped what we were doing and headed for the Main Hanger. Remembering the “2 minute evacuation” – 200 or more of us. As I reached the hanger door I remembered that my jacket was hanging by the jig that I was working on. A “Fiver” ( £5) was in a wallet in it. Knowing the worth of that “Fiver” to me it was a fortune in those days (£271.43- researched) , I turned and raced back through the “SPITFIRE” jigs and grabbed my jacket and then back to the hanger door. By then there was nobody in sight, just myself, stood in the entrance of the open hanger door.

I looked up at the sky and there, flying very low, were 5 twin engine German Bombers coming straight towards me with their bomb doors open and the first bomber had released his bombs. As they came careering down so the other bombers released their bombs, so at that moment I could see at least 20 bombs coming straight for me! The leading bomber by then passed right over me about 500ft up. The pilot looked over the side of his plane and we both looked at each other for a split second before disappearing over the hanger. He wore a leather helmet which I could see quite clearly as he was so low.

In these split seconds the leading bombers bombs were very close. I looked at the nearest one to me which was about to enter the concrete 100ft away or less. My thoughts were “ I’m going to die” , so I just as well run. As I ran I still looked back to see what would happen. Now the bomb had vanished into the concrete. Suddenly the concrete split in all directions and there was a great red and black flame burst through. I looked no more, I was lifted off the ground by a terrific blast and thrown about 100 ft into the entrance of a shelter, where I lay until all the other bombs had dropped, going up and down like a jelly bean.

Then there was a deathly silence ….We knew they had gone.

Luckily I was only bruised so we scrambled out of the shelter. Finding the shelter next to us had been hit and the crater was filling up with water with people trapped we raced to a gun emplacement and collected all the sand bags we could to stop the water filling the crater, which we did.

At the same time over a little road and by the small railway bridge was another crater and buried up to his neck was one of the lads. When they carefully clawed him out they found he was holding the hand of another mate below him. They desperately dug him and saved him before he had suffocated.

By then the place was alive with civil defence men so we gathered our cycles and rode for home after being told to go. The following morning we returned to work to be told to look for bodies among the shelters on the otherside of the railway line which ran alongside our factory. As I wandered along the shelters I noticed a small patch of blue in the thick clay. I began to remove the clay with my fingers and suddenly realised a body was under there. Calling my mates we carefully scraped the muddy clay and found one of the lads. He was laid face down , his head was resting on his arm as if he was asleep. There was no visible signs of injury, but he had died through suffocation.

This is one of the incidents which stays with me.

We then returned to the factory which was still intact, but smashed etc. and continued on the “SPITFIRES” But on the Thursday (26th Sept 1940 – researched) the “Imminent Danger” warning blared again. This time with no hesitation we headed for the farthest point away from the factory and shelters which were already damaged. We got as far as Pear Tree Green, approx. 400 yards from the factory before the first bombs came screaming down. We lay flat on our stomachs on the open green. While laying there the bombs began to drop and we began to bounce up and down again.

Looking to my right as I lay there I could see about a 100 yards away, a balloon barrage winch attached to a lorry and the balloon cable stretching skywards. Around the lorry were 3 RAF men and 2 WAAFS standing there. Then came a terrific explosion . When I gathered myself I looked again to where the lorry and RAF people were. There was nothing. It was a direct hit on them.

As we lay there, with the bombs still dropping, I noticed someone’s head pop up from some distance away and shout “come over here”. We crawled on our stomachs and found it was someone’s back garden, with an Anderson shelter buried in it. We crawled in and found a man and his wife sitting in there. It was very dark in there but they had 5 candles lit on a ledge. Suddenly there was a terrific blast close at hand and out went all the candles. We laid there for some time bouncing about once more.

Then there was silence…..We knew they had gone!!!!

On coming out of the shelter we looked towards our “SPITFIRE FACTORY” it was in ruins and smouldering. There were dozens of civil defence people milling about. We knew our bicycles would be destroyed so we started the long trek home, muddy and bewildered with no chance of a thumbing a lift, only the well off had cars.”